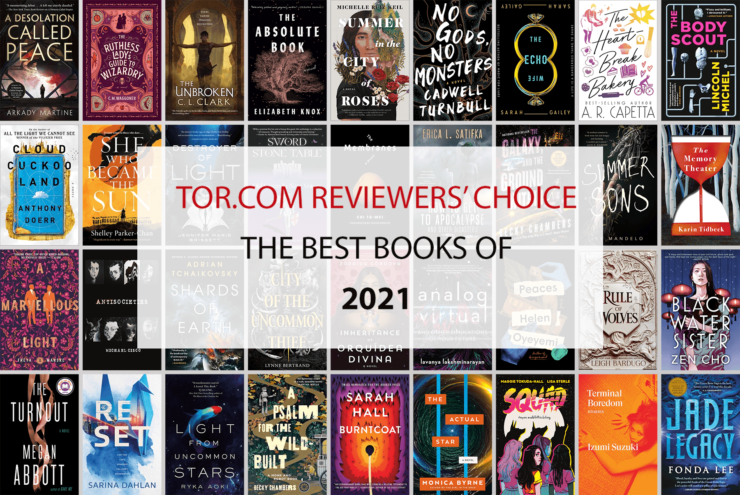

Every year we’re blown away by the consistently amazing book releases in the genres of science fiction, fantasy, young adult, and beyond—and 2021 raised the bar even further. Our reviewers each picked their top contenders for the best books of the year, ranging from hopepunk to fantasy romance, and alternate history to gothic horror. We’ve got high society magicians, retired starship captains, family ghosts, and much more.

Below, Tor.com’s regular book reviewers talk about notable titles they read in 2021—leave your own additions in the comments!

The Galaxy, and the Ground Within. I’m a big Becky Chambers fan, and her final installment in her Wayfarers series gave me the warm sci-fi hug I needed in 2021. The story focuses on a group of aliens stuck at a waystation longer than they expected—something that also resonates in 2021—and includes the heart and hope found in all her Wayfarer books. I’m sorry to see the series end, but am also enjoying her new Monk & Robot series, the first of which—A Psalm for the Wild-Built—also came out this year.

Another book that marks the end of a series is Leigh Bardugo’s Rule of Wolves. This was the last book in the Grishaverse we’ll get for awhile, and it was a satisfying farewell to some of my favorite characters. Last but not least, I really enjoyed the audiobook of C. M. Waggoner’s The Ruthless Lady’s Guide to Wizardry. I’m a sucker for anything Victorian-like, and the protagonist was my kind of ruthless, magical lady whose lovely romance with a woman of high society (who also happens to be half-troll) was the core of the book much more than the plot. That, however, is more than fine by me.

—Vanessa Armstrong

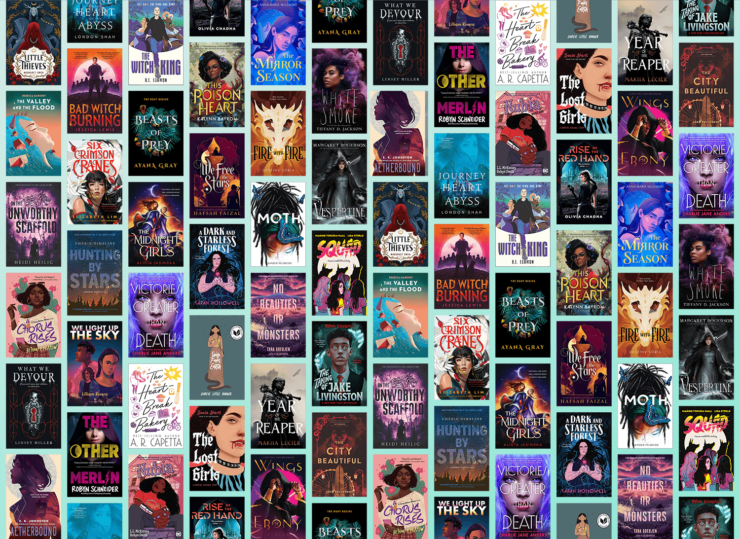

Last year, my reading took a big hit, for what I hope are obvious reasons. This year, however, I feel like all I’ve done is read. Most of my time is spent reading or listening to an audiobook, a steady mix of queer romance novels and lots of YA and adult speculative fiction. Out of the 170+ (!) books I’ve read this year, these are the stories that have attached themselves to my brain like a barnacle on the hull of a ship.

I read a ton of short speculative fiction every year, so picking my favorite always feels like an impossible task. I went back and reexamined all of the pieces that have made it onto my monthly Must Read column here at Tordotcom, and out of all of them Sloane Leong’s “Mouth & Marsh, Silver & Song” is my pick for this Reviewer’s Choice. This story, from the 87th issue of Fireside, made it to my January spotlight, and for good reason. The plot and characters are compelling, but it’s the writing itself that is truly astonishing. Sloane has talent practically bursting out of her, if this story is any indication.

The Echo Wife by Sarah Gailey was an incredible work of science fiction, but it’s the audiobook version narrated by Xe Sands that I can’t stop thinking about. Sarah is an author I will follow anywhere; likewise Xe is a narrator I will follow anywhere. Between the two of them, this book took over my life for the week I listened to it. Even now, months after finishing it, that devastating ending—and specifically the way Xe read it—haunts me.

Few books made me feel as truly seen as The Heartbreak Bakery by A.R. Capetta did. Syd’s journey to figure out what pronouns fit, if any, and Harley’s ever-shifting pronouns reflected through what pronoun pin they’re wearing. The way A.R. explores gender and queerness and the intersections therein. How communities and found families can be just as important, or even more so, as the family you were born into. This is a YA fantasy novel I’ll be thinking about for a long time to come.

I was sold on Maggie Tokuda-Hall and Lisa Sterle’s YA graphic novel Squad the moment I heard it was about queer teen werewolves. It more than lived up to its premise. It was ferocious and sharp in the way only young adult fiction can be. There wasn’t a single thing I didn’t love about it, and hope against hope this isn’t the only graphic novel partnership we get between Maggie and Lisa.

Shout outs to A Snake Falls to Earth by Darcie Little Badger, She Who Became the Sun by Shelley Parker-Chan, The Book of Accidents by Chuck Wendig (and the audiobook version read by Xe Sands and George Newbern), After the Dragons by Cynthia Zhang, and The Witness for the Dead by Katherine Addison. And for short fiction, “10 Steps to a Whole New You” by Tonya Liburd, “The Night Farmers’ Museum” by Alisa Alering, and “If the Martians Have Magic” by P. Djèlí Clark.

—Alex Brown

Picking only three titles a year is a truly impossible task, so I’ll cheat as usual. Here are some stand-out titles I’d love to highlight: Flowers For The Sea by Zin E. Rocklyn, A Psalm for the Wild-Built by Becky Chambers, Fireheart Tiger by Aliette de Bodard, Sorrowland by Rivers Solomon, Defekt by Nino Cipri, Comfort Me With Apples by Catherynne Valente, and The World Gives Way by Marissa Levien. I loved each one of these stories and ferociously recommend them. As for my three main picks, each of them broke my brain and mended my heart at the same time and left me changed.

Light From Uncommon Stars by Ryka Aoki: I can honestly say I’ve never encountered a book like this one. Light from Uncommon Stars is a true wonder of a novel, the kind of book that pushes the boundaries of what exactly a novel can do and then does so with aplomb, grace, and worldbuilding, characterization, and prose that absolutely shine like a star. A story of found family, queerness, identity, music, devils, starships, donuts, and so much more, Aoki’s luminous novel about trans violinist Katrina Nguyen, her infernal teacher Shizuka Satomi (the Queen of Hell, thank you), and Shizuka’s girlfriend, Captain Lan Tran of Starrgate Donut, is delightful, heartbreaking-mending, and a narrative north star for anyone seeking a guiding light to pursue the life, person, or passion they love.

No Gods, No Monsters by Cadwell Turnbull: The second novel from Turnbull, No Gods, No Monsters is a tightrope act of pure skill, as page by page, you understand you’re in the hands of a master storyteller. Taking what 99% of other writers would have focused on and throwing it out the window, Turnbull instead gives us a novel of those in the narrative margins. The people thrown under the bus, hidden in the shadows, everyday communities impacted by the sudden uncanny, the pivot into the strange that’s been living among them their whole life. And just when you think you’ve caught on and know what’s happening, by the end of the novel, the shape of the story is wholly different than what you thought. A thrilling, mind-bending delight that had me grinning and astounded in equal measure.

Jade Legacy by Fonda Lee: After two breathtaking books in the Green Bone Saga, Jade Legacy is Lee’s pièce de resistance as she takes us through a new generation of Green Bones and finally brings the story of Kekon’s two major clans to a close. It takes a divine level of skill to tie every single plot thread in a trilogy together, especially in a story with this level of intricate and complex relationships, magic, politics, and trade that we’ve seen so far. And yet, Lee pulls it off seamlessly, making a Herculean task look effortless; for a book over 600 pages long, you will be riveted to each and every one. One of the strongest endings to a trilogy I’ve ever read, and an accomplishment one for the history books.

—Martin Cahill

In a year that’s abounded with frustration, anger, and depression, one of the few things that hasn’t felt irreparably broken has been reading. When I compared the number of books I’d read last year with the counts from 2021 and 2019, the effects of the pandemic on my mental health came into focus when I saw the substantial dip in 2020. And while “at least the books are good” can feel like cold comfort at times, it could be worse; the books, you know, could be bad.

Among the highlights of my year in reading? Monica Byrne’s The Actual Star, which I wrote about earlier this year. Byrne does a lot here—balancing out three compelling narratives separated by time, finding a space for the sacred in the speculative, and coming up with a radically different vision for a futuristic human society. It’s one of the best examples of worldbuilding I’ve seen in a while. The same could be said for another book I wrote about here this year, Lincoln Michel’s The Body Scout. Both manage the impressive feat of evoking a wider world without getting lost in it.

While we’re talking about great worldbuilding, I’d be remiss if I didn’t praise Jennifer Marie Brissett’s Destroyer of Light. I was a huge admirer of her previous novel Elysium, which brings together formal invention, a deep understanding of coding, and a unique futuristic setting to tell a powerful and unconventional story. Destroyer of Light does all of that, plus throws in one of the most fascinating depictions of an alien civilization I’ve seen since China Miéville’s Embassytown—and also features thought-provoking meditations on colonialism and societal evolution.

In keeping with the theme of writers doing innovative things with language, I’d also like to single out Michael Cisco’s new collection Antisocieties. Cisco’s fiction can move from dreamlike to sobering in the span of a sentence, and whether he’s writing about bizarre fantastical realms or more realistic horrors, his fiction is always eminently compelling. Antisocieties, a collection of stories about isolation and horror, is an ideal place to delve into his work if you haven’t already—a perfect point of entry for a singular writer’s singular writer.

—Tobias Carroll

Out of all the books I read during this wretchedly strange year, the one that truly spoke to me on a visceral and vicarious level was Lee Mandelo’s Summer Sons .This book was a southern scream, a furious reproach of self-hatred, classism, and growing up looking over your shoulder. With gorgeous line-writing and a focused look at the relationships that build and break between men, all tied up in a haunting ghost story, Summer Sons is about friendship and denial in all the worst, best, most destructive ways. This book was really about the power of anger and spite, and this year I needed that.

A book that is the thematic polar opposite of Summer Sons was A Psalm for the Wild Built, by Becky Chambers. Chambers’ work is charming, a wonderful exploration of a post-capitalistic, post-post-apocalyptic society that has found ways to move past the climate crises it caused. As a monk and a robot travel the forested mountains, talking about life, purpose, and programming. With lush descriptions of science fiction inventions and deep interiority, this is a book about being with yourself and coming to terms with not being okay… and finally, moving past whatever was holding you back.

—Linda Codega

Perhaps it’s fitting that after several years of intense grief and rebuilding, three of my favorite reads of 2021 wrestle with inheritance. Ryka Aoki’s Light From Uncommon Stars is a wild and wondrous love letter to trans women of color, to immigrants, to music and to found family. Zoraida Córdova’s The Inheritance of Orquidea Divina weaves a lush, lyric tapestry of magic and perseverance across generations. Freya Marske’s A Marvellous Light is a desperately romantic magical adventure, and it’s also about the way being truly seen by the right person can make us reimagine how we feel about ourselves, and how we envision building our futures. Each of these books explores the raw and complex tenderness of remaking yourself after tragedy, trauma, and betrayal, and they do it with beautiful, propulsive prose and some of my newfound favorite characters of all time.

Shoutouts to several other books I loved just as much, most of which I got to rave about on Tordotcom already: Isabel Yap’s Never Have I Ever, Nghi Vo’s The Chosen and the Beautiful, Joan He’s The Ones We’re Meant to Find, Zoe Hana Mikuta’s Gearbreakers, S. Qiouyi Lu’s In the Watchful City, and Charlie Jane Anders’ Victories Greater Than Death. It was an absolutely kickass year for SFF, and I’m extremely grateful for all of these authors and their spectacular, intricate works of imagination.

—Maya Gittelman

Elizabeth Knox’s The Absolute Book came to the United States more than a year after its appearance in New Zealand; this novel, a twisty combination of epic fantasy and thriller, was worth the wait.

Not every book arrives overseas as quickly as it deserves: American readers are still waiting for a stateside publication of Alan Garner’s Treacle Walker, his first novel since his 2012 masterpiece Boneland. This latest book, slim and spare and mysterious, isn’t where I’d start with Garner—it’s too much in conversation with the author’s past work and with his life story—but I know I will be re-reading it soon.

Helen Oyeyemi’s Peaces is inscrutable and enthralling, while the six-hundred pages of Anthony Doerr’s Cloud Cuckoo Land flew by in three or four rapt sittings.

As ever, there are several books that might have made the list, if only I’d had time to read them. Avram Davidson’s posthumous novel Beer! Beer! Beer! qualifies here, as do Ada Palmer’s Perhaps the Stars, Kazuo Ishiguro’s Klara and the Sun, and Katherine Addison’s The Witness for the Dead.

—Matthew Keeley

When I settled in to peruse my list of “books read 2021” two things became immediately clear. The first is that I wrote and defended doctoral exams this year and the second is that I myself debuted in the fall… so I didn’t functionally read any fiction at all for several months. Oops? But of those books I made it to in 2021, often in a dazed scramble, there are a handful I’d like to bump to the top of folks’ winter reading lists.

The first two books haunted my brainspace long after I finished reading and must be noted again for their sheer fucking awesomeness: She Who Became the Sun by Shelley Parker-Chan and The Echo Wife by Sarah Gailey. Parker-Chan and Gailey both engage in brilliant, incisive ways with the messes of ethics, gender, queerness, and hunger in ways that scratched at my bones. I adored them; I saw myself clearer through the lenses of their art. I also read lots of books in translation, some of which I covered here for Queering SFF. Two of those are of particular historical significance, available for the first time to Anglophone readers: Izumi Suzuki’s Terminal Boredom and The Membranes by Chi Ta-Wei.

And then there’s all the books that I’d stuff broadly into the category “queer fiction and nonfiction,” which I will now shake at you-the-audience in a quick and dirty list as follows: Kink ed. by Garth Greenwell and R.O. Kwon, 100 Boyfriends by Brontez Purnell, Trans Care by Hil Malatino, and A Dirty South Manifesto: Sexual Resistance and Imagination in the New South by L. H. Stallings. Something for everyone, if everyone wants to read about queer sexuality and politics!

—Lee Mandelo

Monica Byrne’s The Actual Star is startlingly good. Intelligent, emotionally astute and so well planned that reading it feels simultaneously effortless and deeply engaging. Set across three timelines (the Mayan empire, modern day and a utopian future), it is about identity, societal evolution, and about what makes us human and ties us together, inevitably and across the span of thousands of years and miles. This is a book that makes you want to hurtle through it, swallowing its huge ideas whole, but it also makes you want to savour it slowly. That push-pull is what makes for such an engaging, dynamic reading.

Zen Cho’s Black Water Sister is an unabashedly Malaysian story, and for that it has my heart. It’s a fun, smart and funny thriller set in Penang, about a young woman who returns to Malaysia a little lost in life, to find that not just is she being haunted by her grandmother, she’s also being pushed into helping the dead settle some very important personal matters. Not once does Cho pander to her audience. Not once does she write with anything less than true authenticity to the voices she’s known, and the world she’s grown up in. Family, identity, faith and adulthood: Black Water Sister effortlessly encapsulates all this in a creepy, fast paced modern day ghost story.

Any year Megan Abbott has a new book out is a year that a Megan Abbott book will be on my best of lists. This year she gave us the slow burn ballet school thriller The Turnout. The Durant sisters were raised to be ballerinas, always together, always focused inwards and always knowing that they’d continue their mother’s teaching. Now they run the school they’ve inherited, everything remaining seemingly the same until an accident sets off a chain of events that throw their lives into chaos. As always with Abbott, there are the weighty (but so perfectly balanced) themes of sexuality, motherhood, womanhood and power. As always, Abbott’s writing is beautifully taut and lean, her words vibrating with tension constantly, as the narrative moves hypnotically around the lives of the women, and those who love them.

—Mahvesh Murad

Erica Satifka’s How to Get to Apocalypse and Other Disasters (2021) is her first collection, hopefully the first of many. Every piece is excellent, but there are a few common threads: mostly near future science fiction, featuring ordinary, ‘non-extraordinary’ people, facing unsettling situations. They’re exquisite and character-focused, but, above and beyond that, Satifka is possibly the finest speculative world-builder of a generation. These are not simple ‘one twist’ SF tales; each of these stories features layer upon layer of speculative imagination. But rather than distracting from the plot, or the characters, Satifka interweaves the science fictional elements so insightfully that they feel entirely natural; they’re so organic that they never overpower the rest of the story. This collection is an absolute masterclass in writing science fiction.

Sword Stone Table (2021) edited by Swapna Krishna and Jenn Northington, is an exciting ‘reclamation’ of the Arthurian mythic cycle. Divided into three parts, it reveals the universality of the stories of King Arthur and the Round Table. The anthology proves, in many ways, how the ‘once and future king’ truly is a transcendent canon of stories. Although the book contains many clever retellings—Arthur on Mars! Arthur Coffeeshop AU!—the finest entries go even further, and explore the nature of myth itself. Roshani Chokshi’s “Passing Fair and Young”, for example, is a powerful discussion of myth and agency, as told from the point of view of a “secondary” character.

Lavanya Lakshminarayan’s Analog / Virtual (2020) is simply staggering. Following the collapse of, well, everything, Bangalore is now ‘Apex City’, a world where the ‘Virtual’ elite compete in a strictly graded social hierarchy—one based on the rigid application of the bell curve. Success means ascent to the highest reaches, with unlimited wealth and power. Meanwhile, the Analogs live in an outcast society, devoid of even basic technology. Told as a series of cleverly interconnected short stories, Analog / Virtual shows us Apex City from every perspective: the rebel, the celebrity influencer, the ruthless social climber, the entertainer, the secret doubter, the addict. Science fiction on a grand scale, brought together through narrative pointillism; as the stories build, the reader starts to see it all come together. As the true horror of Apex City begins to emerge, so does a sense of hope, as Analog / Virtual remains committed to showing all sides of human nature.

—Jared Shurin

The books that stuck with me this year were the ones that made me lose all sense of time, like Sarah Hall’s Burntcoat, which I devoured with a heady mix of dread and wonder. The dread because loss pervades this book from the start; the wonder because even when I was sobbing at the end, I felt awe, and love, and hope. It’s a book about art and it is a work of art.

Lynn Bertrand’s City of the Uncommon Thief is a book I beg you to read if you like mysterious cities; this one is filled with craftspeople whose vision of their world is limited and peculiar. They have so much to learn and so much to show you; their stories encompass a whole library worth of tales, of strange magic, of inner selves and all the kinds of family. This is the kind of book you fall into, and crawl back out of dazed.

I loved a story set in my own city in Michelle Ruiz Keil’s lush and mythic Summer in the City of Roses; I loved the strange landscapes of Karin Tidbeck’s quietly monumental The Memory Theater. And I sank entirely into the hotel rooms and London pubs of Sarvat Hasin’s The Giant Dark (a book I am sorry to say isn’t published in the US). Told in the alternating perspectives of a lover, his musician ex, and the Greek chorus of her ravenous, adoring fans, The Giant Dark gorgeously digs into heartache and yearning and loss, turning secrets and mundane moments into a story both vibrantly detailed and eerily familiar. (There’s a vampire love story in it, too.)

—Molly Templeton

While last year, one particular book stood head and shoulders above the rest for me, 2021 has turned out to be more of an ensemble year, with a lot of books jockeying for my attention and love and trying to make this final list. I could have doubled its length and written a couple of thousand words, easily.

A poignant story on the costs of making a society that endures after an apocalypse, the haunting power of Sarah Dahlan’s Reset holds with me still. A melding of memory, art, happiness and ultimately the costs of love, the story is intimate on the page, even as it explores its central characters to great and moving depths. Reader, I was moved by the author’s work.

In a alternate history/fantasy novel that reminds me of works such as The Water Margin (or, say Red Cliff), Shelley Parker-Chan’s She Who Became the Sun wove for me a story of an alternate world where a young woman steals the destiny of her brother in late Yuan Dynasty China… a destiny that, in her desperation to survive and find a life for herself, will lead her to oppose that dying but still powerful polity. And that is but one major strand in a story of dynastic struggles and scenes both intimate and epic

Finally, and the best for last, was Adrian Tchaikovsky’s Shards of Earth. The author is a major talent, seemingly trying to write in every subgenre of SFF that exists. In Shards of Earth, he goes for a widescale space opera that, in terms of physical breadth as opposed to temporal, exceeds his Children of Time. Shards of Earth features obtuse aliens turning planets into uninhabitable works of art, a found family on a ramshackle spaceship, political biting and factions even as humanity, clawed back from extinction, needs to cooperate against the next threat, and so much more.

—Paul Weimer

Considering how much I adored Arkady Martine’s A Memory Called Empire, how could A Desolation Called Peace be anything but spectacular? Yet I love how the latest trip to Teixcalaan didn’t try to duplicate its predecessor’s success. Memory can be distilled down to a gorgeous scrap of poetry; Desolation introduces an alien language that makes translators vomit. It’s just a wonderfully chaotic romp full of new perspectives. Like Mahit and both Yskandrs awkwardly fitting themselves into one new personality, this sequel expanded and reshaped what a Teixcalaan novel can be.

Considering how much I adored Arkady Martine’s A Memory Called Empire, how could A Desolation Called Peace be anything but spectacular? Yet I love how the latest trip to Teixcalaan didn’t try to duplicate its predecessor’s success. Memory can be distilled down to a gorgeous scrap of poetry; Desolation introduces an alien language that makes translators vomit. It’s just a wonderfully chaotic romp full of new perspectives. Like Mahit and both Yskandrs awkwardly fitting themselves into one new personality, this sequel expanded and reshaped what a Teixcalaan novel can be.

Then there was C.L. Clark’s whip-smart The Unbroken, which has such impressively lived-in fantasy worldbuilding for a debut. That all comes down to Touraine—soldier, spy, easily my favorite SFF character of the year. The court machinations and rebel intrigues were satisfyingly multifaceted and never felt tropey, and the chemistry between Touraine and princess Luca… whew. Not only am I here for this year’s sapphic fantasy, but cannot get enough of the morally grey romances.

Cracking the spine of Monica Byrne’s ambitious The Actual Star felt intensely familiar, thanks to her Patreon detailing her inspired vision for a nomadic society in 3012. But even those viajeras a thousand years in the future struggle to absorb so much information, mentally braiding disparate strands of data together in order to find the connections between them. Reading The Actual Star felt the same, even for someone who had already accepted the Laviaja pitch: The reader can see Byrne’s meticulous structuring (braiding three time periods), but you also have to entirely give your trust over, following her into the metaphorical darkness of a Belizean cave. Never fear, because Byrne has planned for that, too, plotting this epic to match the transcendent three phases of cave exploration; it’s nothing short of masterful.

—Natalie Zutter